This page at a glance …..

The church exists to make disciples. That is the task that Jesus left us. And disciples are people who follow Jesus’ teachings, not just believe in him.

To follow Jesus’ teachings, we need to learn about him and what he expects of us, and then we need to be challenged and inspired to commit to believing and following him. We need to be taught, and our lives need to be transformed.

What if we were going about this in a way that was contrary to the way God made us?

The human brain has to deal with an enormous amount of input, from our 5 senses and from our nervous system. Only a small amount of this information is retained in long term memory, the rest is forgotten. Some is forgotten immediately, but the brain processes other information to decide whether to retain it, what other memories to link it to, and how it will respond.

If we receive too much important information for more than about 10 minutes, our brain starts to get fatigued, doesn’t properly process, and some information is lost. Information is more likely to be retained and acted on if (1) we are interested and actively engaged, (2) we receive it via more than one of our senses, (3) we discuss it with others to assist in processing it, (4) we speak it out to reinforce it, and (5) we put it into practice immediately.

Sermons and lectures have almost none of these attributes, and studies show that only a small amount of any sermon is retained and acted on, generally from the first 10 minutes. Sermons tend to make people passive. It makes no sense to use a method that is not suited to how our brains operate.

If we want christians, and the church, to grow and be active in their faith, we need to use active or participatory learning methods. There are many ways we could do this.

It’s time to reconsider the sermon

The sermon is generally the most important element in Protestant church services. (Most sermons take between 25 and 45 minutes.) But there are serious doubts about its effectiveness and Biblical basis.

Here is a summary of research and expert opinion I have found on the subject.

Adult learning

There is plenty of research and conclusions on how adults learn best. One of the most respected experts on adult education was the late Malcolm Knowles, who came to these conclusions:

- Adults do not need so much to be taught as to have someone facilitate their self-learning, leaving them able to learn in their own way.

- Learning should be related to life experiences and current knowledge.

- Adults learn best when they have a clear goal and the learning is relevant and practically useful.

- Adults learn best when they are motivated to learn and the process is positive and encouraging , and treats them with respect.

Ways people learn

Some people tell us that people learn in different ways:

- visual: via graphs, pictures, reading and taking notes, etc,

- aural: via listening and discussing, and

- experiential (or kinesthetic): via touching, moving, role plays, field trips and experiencing.

But it seems that the experts say this is a myth, commonly believed but actually not helpful.

Studies show that people don’t have different learning styles, rather the most effective learning style is most often determined by the information being taught, not by the person. Visual information is best learned visually, sound information is best learnt aurally. But most information is understanding, and that is best given using multiple senses. It may be true each person has a personal preference in how they like to receive information, but this is more likely because their interest is in information that is best transmitted that way.

People will use many different ways of learning, so using more than one at a time is most effective. For example (and generalising), people remember only 20% of what they hear, 75% of what they see and hear, and 90% of what they hear, see and do.

Katie Driver gives similar, though ‘worse’, statistics – adults retain 90% of what they learn if they teach it to someone else, and have immediate application of what they learn; 75% of what they learn when they practice it; 50% of what they discuss in a group; 30% of what they see demonstrated; 20% of what they see and hear in audio-visual teaching; 10% of what they learn through reading; and 5% of what they learn through lecture.

How the brain remembers

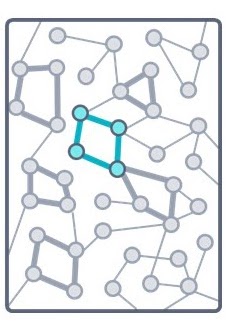

There are two distinct aspects to our memory – short term and long term memory 1. Long term memory is all the information we know, even if we sometimes struggle to recall it. Short term memory holds the information we’re currently working with or thinking about. This can be new information delivered by our senses or old information retrieved from long-term memory.

Short term memory

Our senses receive an enormous amount of information, much more than we want or need to live and think. Fortunately, the brain filters out most of this information before we are even conscious of it. For example, if we are standing on the sidelines watching a football match, our eyes will receive input from each separate blade of grass in our field of view. But since we are not interested in each blade, just the players and the ball, we only see the grass as a mass of green. Our brain has filtered out the details of the individual blades.

The remaining input from our senses is then stored, briefly (up to 30 seconds), in short term memory (sometimes called working memory), before it is replaced by newer inputs (as illustrated in this TED talk). Short term memory can only retain about 4-8 items at one time, so if the brain doesn’t process these inputs quickly, they will be lost. There are at least two ways retention can be improved:

- We can retain short term memories by repeating or rehearsing them. For example, we may several times repeat a phone number we have been given verbally so we retain it long enough to enter it into our phone.

- Our brains can “chunk” information. So while we may struggle to remember a 10 digit phone number (e.g. 0123456789) as ten individual digits, we may remember it as 3 chunks of digits (0123 456 789).

If new information in short term memory is to be remembered, it has to be passed into long term memory before it is replaced by even newer input. Processing in short term memory is the only way information can be stored in long term memory.

Long term memory

The brain processes this information via two steps:

1. Encoding

First the raw information must be encoded – that is, the brain links all the relevant information together to form a memory, actually creating new synapses.

At this stage, the memory isn’t connected to other knowledge – therefore we won’t have a good understanding of the concept, and we will find it more difficult to recall it.

The brain gives priority to memories that:

- have a strong emotional content;

- have been rehearsed over and again in short term memory;

- are important, memorable or personally meaningful; or

- the memory can be associated with something already in memory (i.e. something we already understand), whereas things that are difficult to understand will be given lower priority.

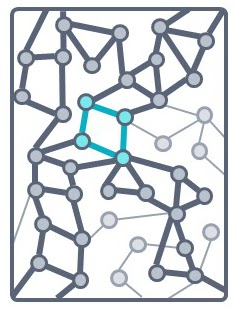

2. Consolidating or understanding

The memories thus preserved are then consolidated by being stored in long term memory, and linked to other memories already there. We then have an understanding of the concept, in terms of concepts and words that we already know and understand.

Prior knowledge is very important. If existing information is recalled just prior to learning new information, the new information will be more readily consolidated.

These processes can occur quickly if the information is straightforward, but can take days if the information is unusual or creates problems by being new, unusual or contrary to other knowledge in long term memory. Processing can be fatiguing – teens and adults can generally only process new information for about 10-20 minutes before they become fatigued, and further information can be lost.

Further consolidation occurs during sleep, and is ongoing through life. Memories are strengthened when used and weakened if unused.

Using stored information

Initially, we may find it takes effort to remember and use new information. But two more processes assist this.

3. Use

If we use the new information, the brain establishes more neural pathways that connect our new memory to a wider set of information. This makes it easier for us to recall the new memory when we need it, because it is connected to other information.

And so when we think of one item we will likely think of the other as well. We will thus be more able to apply the information usefully.

Thus it is important that new information be used as soon as possible so it will be remembered, able to be recalled and useful. However, if a memory becomes weak through lack of use, it can be reactivated through use.

4. Mastery

With repeated use over time, in different situations, the information will be so well connected in our brains that it will come to mind quickly and automatically when needed.

As we use our new understanding in various contexts, the pathways in the brain can be simplified and made more robust and efficient.

We can see that repetition, especially in different situations and contexts, is an important part of making information useful.

Repetition can occur if we repeat information to ourselves, or tell someone else about it, or come into situations where we apply the information in some way.

Application to sermons and learning

All this has obvious implications for learning and remembering. If short term memory is overloaded with too many new items of information, or if information processing is required for more than about 15 minutes, overload or fatigue will occur and some items are not remembered.

And if people don’t have opportunity to practice or rehearse what they have learned, it will not be useful information and may not be remembered.

We cannot expect people to learn in ways contrary to the way their brain functions!

University studies on learning

Much of the research has been done at universities, where research has focused on some broad themes.

University lectures don’t rate

A recent Scientific American reported on a paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences which examined hundreds of studies on the effectiveness of lecturing in universities.

When compared to more participatory learning, lectures rated very poorly. “Learners who are subjected to the one-way mode of lecture-based teaching have a 1.5 times higher failure rate than those who are allowed more participative methods.” Students found it difficult to concentrate for the entire lecture, and often became passive.

One study found student scores at the end of a semester of lectures were only 14% higher than they had been at the start!

This isn’t surprising. “Cognitive scientists determined that people’s short-term memory is very limited – it can only process so much at once. A lot of the information presented in a typical lecture comes at students too fast and is quickly forgotten.”

“lecturing isn’t the best method to get students thinking and learning.”

Attention spans

Many studies have found that most adults can focus for about 15-20 minutes maximum before they start to lose attention (see The National Teaching and Learning Forum, K Mortensen, quoted by Thomas Hudgins and Seth Norberg).

However it isn’t quite as simple as this. Some studies show that attention waxes and wanes through a university lecture, typically:

- An initial 3-5 minutes to settle down,

- 10-18 minutes optimum focus,

- a lapse in concentration followed by a return to concentration again, and

- further cycles of shorter and shorter periods of focus then lapse (perhaps every 3-4 minutes in the end).

Other more recent studies suggest a similar pattern of concentration then lapse, but the lapses are less regular or predictable, more frequent and briefer.

Information retention

Students remember best what the hear first. Immediately after a lecture, students remembered 70% of what was presented in the first 10 minutes, but only 20% of what was presented in the last ten minutes.

Within an hour of hearing something, less than half of what is remembered will be retained. Retention reduces even more in the days following.

Active or participatory learning

Cognitive research has found that people learn better when they’re actively engaged. People learn by practicing, with feedback to tell them what they’re doing right and wrong and how to get better. They also learn when they have to explain something to someone else.

Information retention can be significantly improved by adopting active learning teaching methods that provide opportunities for students to pause and reflect/discuss briefly at times during a lecture, or at the beginning and end, to work collaboratively or to participate interactively.

Active learning works

Studies show that active learning can significantly increase students’ abilities to learn and remember – more than doubling retention from as low as 12-23% up to almost 50%.

Principles of active learning

This understanding of the brain and learning has led to several principles of active learning being developed:

- Utilise more than one of the senses and hence more than one of the learning styles.

- Encourage active participation by the learners, so that information is more readily processed and more easily assembled into mental models, which make sense of the information.

- Provide opportunities to put information into practice. Learning facts and learning to do something are very different processes, and learners need to practice applying facts to life.

- People learn better when they learn with others and can discuss.

- People learn much more when they have to articulate what they have learnt.

- Don’t overload working memory (i.e. don’t give too much information at once) or information may be lost.

- Learners need to get enough sleep – to process yesterday’s information and to be awake for tomorrow’s.

Active learning techniques that work

Techniques that fulfil some of these criteria include:

- Guided problem solving where students are given an example to work through in class and guided by the lecturer.

- Discussion in pairs or small groups. This may include thinking through specific questions asked by the teacher.

- Learners do their own research, generally online, and report back, and the matter is discussed. Learning by teaching can be very effective.

- Use videos, games or role plays followed by questions.

- Follow teaching with tests.

Peer instruction

One method that is effective is Peer Instruction. It can work in several ways:

After lecturing on a topic for 15-20 minutes, the lecturer stops and asks a multiple-choice format ‘quiz question’ that tests students’ understanding of the topic under discussion. Students vote on the right answer, and the lecture is adjusted accordingly. If there is poor understanding, the students are asked to discuss the question with their neighbours, and a second vote is taken. The results are almost always far better.

Alternatively, the discussion can be held at the beginning, to awaken interest in the subject, or at any point during the lecture. It turns out that those who understand the topic can generally explain it better to their friends than the expert lecturer can.

“The “convince-your-neighbour’ sessions allow for valuable peer interaction between students. This promotes active engagement: students have to do more than passively assimilate material, they must think about it and try to explain it to someone else.”

Use of Peer Instruction improves student learning and understanding.

Reinforcing what has been learnt

Studies show that simply re-reading or re-hearing what we have learnt is not very helpful in remembering. But if we practice recalling what we have learnt, we strengthen and reinforce the retrieval pathway, and can remember better in the future. That is why discussion, telling others, problem solving and tests can all assist learning.

If lectures must be used:

- Introduce the most important facts at the start (when they are most likely to be remembered) and then go over them in more detail.

- Use a variety of approaches – visuals, arresting stories, humour, illustrations, examples, etc.

- Half way through, review what has been covered so far, perhaps via group discussion.

- Break talks up into segments of no more than 20 minutes, with breaks of perhaps 5 minutes when learners can review what has been learnt or work through an example. Sometimes breaks should be a complete break with the subject.

- Let non-experts lecture. It may sound crazy, but studies show that people who have just learn something communicate better to new learners than do experts, because they can remember how hard it was for them.

Active learning in practice

Most of these principles are quite clear and understandable. But secular educators have recognised that they need to be developed into programs and curricula. And so the concepts of active learning and participatory learning have been developed and implemented in many ways:

- School learning has been modified from the older passive listening and ‘rote learning’ to more active, experiential and involving forms of learning.

- Many universities and other tertiary institutions now encourage and assist staff in such diverse fields as Chemistry and Philosophy to use active learning techniques – and also undertake research.

- Teachers and educators are commonly trained in these approaches.

- Business and community training also uses these approaches.

- Many textbooks have been written on the subject – including How People Learn, Experience and Education, Understanding and Facilitating Adult Learning and Learning in Adulthood.

Transformational teaching

Educators are now developing the concept of transformational teaching, in which students are coached by their teacher as they actively participate in:

- learning together through new shared experiences, facing and resolving problems and developing a future vision of where their learning will take them;

- facing challenges which assist in their personal development and in developing a positive attitude to learning; and

- developing a vision for what they will achieve together.

Transformational teaching is seen as an over-arching approach that encompasses the insights of active and participatory learning and peer instruction, and has a lot of relevance to discipleship in churches.

So what can churches learn from all this?

The goal of the church is the mission of God – an action to bring about change. That undoubtedly requires all of us, especially new believers, to learn and grow. But we may well question how important public teaching is for this.

Nevertheless, the fact remains that presently the church makes teaching via sermons one of it’s main activities and (presumably) one of its main strategies for making disciples. Yet it is a teaching method that has been shown to be relatively ineffective!

Sermons are basically lectures, and studies have found that congregation members react similarly to university students. They lose concentration easily, and they learn and understand better if they are actively learning.

Replacing sermons with more interactive learning will be best, but if we must have sermons (and it seems unlikely that preachers will give them up easily, even though they are less effective), they should employ active learning and Peer Instruction approaches.

Learning in churches

Some learning studies have been done in churches:

Attention span & recollection

A study of Catholics in Germany found that “most of the audience tended to pay attention to the sermon in its entirety, although relatively few people actually remembered what they heard”. 60% attended to the sermon in its entirety, 34% gave partial attention, while 6% gave almost no attention. But only 22% had substantial recollection later, 35% had moderate recollection and 43% had little recollection.

Learning and change

In a 2009 New Zealand study, Jenkins & Kavan reviewed the research and commented: “studies have shown that sermons have a minimal influence on listeners”. However they found that while listeners did not learn a great deal, or change their behaviour greatly (objective measures used in some other studies) because of a sermon, they responded positively to sermons which appealed to them emotionally.

This US study obtained similar results. Listeners valued sermons and considered them the part of the service most likely to help them in their spiritual growth; the study found that sermons aimed at specific changes in the listeners are the most effective, but nevertheless, “it’s the rare sermon that creates lasting change” while informative sermons are even less effective.

So it seems that teaching sermons are a very poor means of teaching, sermons seeking behavioural change are not very successful, and only sermons which encourage and comfort seem to achieve their goal. This Anabaptist blog suggests that changes in our western culture (“from passive instruction to participatory learning, from paternalism to partnership, from monologue to dialogue, from instruction to interaction …. from linear to non-linear methods of conveying information”) require changes in our teaching methods.

Example: trying something different

“During my message, I asked our folks to find a partner and share their response to a non-threatening question. Initially, my inquiry was met with blank stares, but slowly everyone began to partner up. Faces that had been somber moments before broke out in smiles as they engaged in conversation. I let them share for a couple of minutes and then resumed my sermon.”

“After the service people kept talking, many of them finishing the conversations they’d started during my sermon. Also, several people thanked me for preaching the best sermon they said they’d ever heard. Many talked about the steps they were going to take to live out what I had talked about. Woo hoo!”

Sermons in the New Testament

Are sermons recommended in the New Testament, and were they commonly used? The evidence is against this.

Monologue sermons?

I know of no reference in the New Testament to exegetical preaching as we know it today, and few to anything like a sermon.

The ‘sermon on the mount’ (Matthew 5-7) was almost certainly not a sermon in the modern sense. Luke’s gospel gives a lot of the same teachings, but not all in one place, and scholars are generally agreed that Matthew has simply grouped many of Jesus’ teachings into this so-called sermon.

Paul’s talk in Acts 20:7-12 was certainly long (he spoke for most of the night), but it was a rare occurrence and the last time they would see him. Even so, one listener fell asleep with disastrous results!

David Norrington (To Preach or Not to Preach) investigated the New Testament and early church history and concluded that “monologue preaching was present in this period but was used only occasionally rather than regularly. Much more common were discussion, dialogue, interaction and multi-voiced participation.”

The several different Greek words translated “preach” in many Bibles (kerysso, euaggelizo are the most common, but there are several others) are better translated as “proclaim”, “declare”, or “announce”. Greek scholars agree that they are used to describe the proclamation of the good news to the world, and never refer to anything like a modern sermon to a group of believers.

Whenever christian meetings are described (which isn’t very often, e.g. 1 Corinthians 14:26-33, Hebrews 10:25) the believers all minister to and encourage each other, and there doesn’t appear to be any reference to a sermon.

Dialogue

Jesus’ characteristic teaching methods were parable and dialogue (argument or question and answer).

Paul’s missionary work was characterised by a similar two-way method of communication – the Greek word used in Acts 17:2, 17, 18:4, 19, 19:8-9, 20:7, 9, 24:25 indicates dialogue – and he urges all members to be involved in the gatherings of the christian community (e.g. 1 Corinthians 14:26-33).

Learning “on the job”

Jesus did not send his disciples to Bible College, but taught them in the situations of life, as he conducted his ministry (e.g. Mark 9:26-29, Luke 11:27-28, 13:1-5) and by letting them learn on the job (Luke 10:1-12).

Knowledge is two-edged

While Paul clearly valued the knowledge of God and given by the Spirit, he regarded ‘knowledge’ on its own (what we would call ‘head knowledge’) with some suspicion (see e.g. 1 Corinthians 8:1-11) and of less value than other gifts and attainments (e.g. 1 Corinthians 13:2-8). Both Jesus (Matthew 21:28-31) and James (James 1:22-25) condemned knowledge or talk without an appropriate response.

Dependence on sermons is problematic

According to some scholars (e.g. David Norrington), the sermon as a form of oratory first entered the church after christianity became the state religion under Constantine in the early fourth century and the clergy vs laity divide began, perhaps reinforced in the Middle Ages, and emphasised by the Reformation emphasis on teaching the word. It is argued by some that the sermon originated as a way of showcasing the preacher’s oratical gifts rather than teaching the congregation.

There are occasions when a monologue talk may be the best option (e.g. when a gifted visiting teacher is available for a short time to talk on an important topic), but there is little (if any) New Testament justification for weekly monologue, exegetical (knowledge-based) sermons, and some good arguments against them.

Learning vs Discipling

Jesus gave us ‘the great commission’ (Matthew 28:18-20), to “make disciples” and “teach them to obey” his teachings. So our conclusions on sermons should not be based on whether they ‘faithfully teach the word of God’, but whether they are useful in making disciples and assist them to obey Jesus’ teachings. A disciple who is one who follows, under the discipline of his master, not just one who knows the facts.

The evidence from the educators and experience is clear. Monologue sermons keep people passive, do not teach or disciple them very well and thus do not do a lot to fulfil the great commission.

Their main virtue seems to be that they are an efficient way to ensure that the paid minister keeps control of the teaching and speaks to as many people as possible at one time. It has the appearance of efficiency, but is not effective.

Exegetical sermons appear to have the virtue of teaching the Bible, but may fail to connect to daily lives. A New Testament Professor wrote:

“But I wonder if we really are helping people be giving them a prepackaged Bible lesson every week. Are we preparing them for what life will bring their way? Are we teaching them to read and study the Bible for themselves?”

Suggestions to improve or replace monologue sermons

- Teaching must not be an end in itself, but a means to achieve the end of making us all mature obedient followers of Jesus who are making a positive difference in the world.

- Sermonising implies that we can’t learn by reading the Bible and reflecting on life ourselves. Perhaps the time spent in sermons could be better spent in teaching lay people how to learn themselves?

- Teach and disciple using mentoring, which is two-way and experiential.

- Active Learning: “some sort of engagement between the speaker and the audience especially in the form of what some call ‘student active breaks’.”

- Replace the monologue sermon with something that is learner-focused, multi-voiced, open-ended (“be prepared to leave loose ends and to live with uncertainty, to run the risk of allowing people space to think, to reflect, to explore”) and dialogue-based.

- Break things up. Have several shorter talks on different, practical subjects by different people.

- Shorter sermons – much shorter!

- Taking notes, even if they are not kept, may assist people in focusing and processing, though this is a somewhat artificial solution.

- Primary discipleship could be done one-on-one (as practiced by the Navigators), in small groups or simple churches (where everyone can contribute), or by “on the job” apprenticing within ministry teams.

Don’t underestimate the difficulties!

There will likely be resistance from both clergy and laity to making any change away from sermons.

Clergy will lose their position of power and esteem. They will likely feel they are not doing their job, and not equipped to take on more mission-oriented tasks. More effective forms of teaching will be more difficult and time consuming, and will require more personal contact with people. Some will welcome these changes, many will feel threatened by them.

Lay people have come to expect “good teaching” from an expert, and may feel the minister is no longer earning his pay. (One study showed that university students learnt more when active learning methods were used, but they respected their lecturers less.) Sitting passively and not being much challenged may suit many.

Objections

So this is significant and threatening change. It may be resisted by various responses:

“But you are forgetting about the Holy Spirit”

This objection is often made. But are we going to offer God anything less than the best? Should we deliberately use poor methods, trusting him to “fix them up”? If we really believed that the Holy Spirit worked in this way, we would eliminate sermons entirely and just read the scriptures, and rely on the Spirit to teach each person!

“We don’t need any fancy modern educational ideas. All we need is the Word of God!”

But if that is so, why aren’t we dispensing with sermons and just reading the Bible?

“People may not look like they’re listening, but something goes in.”

The studies show that less goes in and even less is remembered and acted on, than if we used a different method.

“People in my congregation tell me how much they appreciate my sermons – they wouldn’t accept change”

Studies show sermons make congregations feel better, but they neither learn much or change much as a result. Pastors who want to equip their congregation for the work of ministry (Ephesians 4:12) instead of keeping them passive and doing most of the ministry themselves, will find ways to make gradual change.

“But I was never taught how to do this”

This is a substantial issue. Instead of teaching preaching, Bible colleges should be teaching education, training and equipping.

In the meantime, most congregations include school teachers who are trained in these things. Pastors should utilise the teachers’ gifts, to gain new skills themselves, and to do team teaching with the trained school teachers.

Making it happen

There is no point in rushing in with massive change, thereby alienating people. A gradual process would surely be better.

- Churches could start with occasional changes for special services, before making changes more regularly.

- Or splitting the sermon into two parts, both by the normal preacher, before sharing the two talks among two different speakers.

- Shorten the sermon a little and give time for a testimony, or sharing by a congregational member, or a report from a ministry team.

- Perhaps begin the changes in one service while other services remain the same, and then allow the revolution to slowly spread.

- Move by steps towards a “magazine service”, where many different elements contribute to the whole – Bible teaching, practical training, testimony, ministry team reports, interviews, meditative prayer, ministry prayer, “worship” (devotion to God), discussion & sharing, etc.

- Many churches, especially in the US, are trying Dinner Church (“table, not stage”) where the gathering is around a meal, thus facilitating sharing, but still including many of the elements of a more traditional service.

- Something similar but more radical is “stations church” (the invention of my friends David and Kylie). “Stations” are set up around the building, each with a different activity – prayer, meditation, lament, lectio divina, song, short talk, discussion, testimony, confession, prayer ministry, etc – and people arrive and go in turn to the activities that most meet their needs on that particular occasion. We have used this approach and found it helpful and popular.

The challenge

I hope and pray that we will realise the importance of improving how we disciple people, and want to be part of a change. And then learn and do what we can!

Further reading:

Church in a Circle blog is the best source I know of practical ideas on more personal and more effective learning and growing in church situations. A few of my favourite posts are:

- 10 reasons to stop sermons and use other learning tools

- Flip the classroom, flip the church

- Let your congregation preach the sermon next Sunday

- 7 ways to turn your passive church service into an active learning experience

- Hidden messages in pulpits and pews

- “One-anothering” in church – setting up situations for mutual ministry

- The results are in – people prefer short sermons followed by discussion

- 10 principles which could transform your church practices – permanently.

- And there’s plenty more – coming soon!

Learning in the brain. Dr. Efrat Furst. Dr Furst’s website is full of useful information on learning (plus the brain diagrams I have used here, with permission).

The role of memory, knowledge and understanding in learning. The Education Hub.

How the brain learns. Training Industry.

Interactive Preaching by Stuart Murray Williams is a good summary and provides some good references.

Stop Lecturing Me! Scientific American.

Transformational Teaching: Theoretical Underpinnings, Basic Principles, and Core Methods. George M. Slavich, University of California and Philip G. Zimbardo, Stanford University. This paper has 237 references supporting its discussion of the benefits of transformational teaching.

Active Learning. Wikipedia.

Active-Learning Ideas for large Classes: Simple to Complex. Faculty Focus.

Why Long Lectures are Ineffective. Time.

Why Nobody Learns Much of Anything at Church: And How to Fix It by Thom & Joani Schultz goes into active learning at some length.

Sermons Most Likely to Succeed: Do sermons actually change beliefs and behavior? An ongoing study reveals hard facts. Centre for Excellence in Congregational Leadership.

Sermon Responses and Preferences in Pentecostal and Mainline Churches. William Jenkins & Heather Kavan.

Note 1. Terminology on this matter is not consistent. Short term memory is sometimes equated with working memory, other times the two are defined differently. In some sources, working memory and intermediate memory make up short term memory. There are many different theoretical understandings. I have used what seems to me to be the most common usage, of short term memory and long term memory, and have only used the term working memory to clarify the references.

Photo Credit: Wiedmaier Flickr via Compfight cc

Diagrams are from Dr. Efrat Furst, and are used with her kind permission.